Gas stoves are a leading source of hazardous indoor air pollution, but they emit only a tiny share of the greenhouse gases that warm the climate. Why, then, have they assumed such a heated role in climate politics?

This debate reignited on Jan. 9 when Richard Trumka Jr., a member of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, told Bloomberg News that the agency planned to consider regulating gas stoves due to concerns about their health effects. “Products that can’t be made safe can be banned,” he noted.

Politicians reacted with overheated outrage, putting gas stove ownership on a par with the right to bear arms and religious freedom. CPSC Chair Alexander Hoehn-Saric tried to douse the uproar, stating that he was “not looking to ban gas stoves” and that his agency “has no proceeding to do so.” Neither does the Biden administration support a ban, a White House spokesperson said.

Nevertheless, congressional Republicans raced to the barricades, introducing bills with titles like the Guard America’s Stoves (GAS) Act and the Stop Trying to Obsessively Vilify Energy (STOVE) Act.

This skirmish may seem like a tempest in a teapot, but it reveals important contours of the battlefield on which climate politics are waged. As I explain in my book, “Confronting Climate Gridlock: How Diplomacy, Technology, and Policy Can Unlock a Clean Energy Future,” gas stoves matter to climate and to the gas industry because they serve as gateway appliances to the dominant residential uses of natural gas: heating and hot water.

Serious health effects

Direct impacts from gas stoves are a much more urgent concern for human health than for Earth’s climate. Gas stoves are a leading indoor source of nitrogen dioxide, or NO₂, which can cause or worsen respiratory illnesses in people who are exposed to it.

For example, scientific studies show that living in a home with a gas stove increases children’s risk of asthma by nearly one-third and contributes to pulmonary disease in adults.

The climate doesn’t care what fuel we use to cook. Gas stoves account for just 0.1% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, even accounting for recent findings of larger than expected household methane leaks. They aren’t a big share of fuel sales either, burning just 3% of the natural gas consumed in homes.

Impeding home electrification

The significance of gas stoves for the climate becomes clearer in the context of the Biden administration’s goal of achieving net-zero U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. This target can only be achieved by curbing fossil fuel use across the economy, including in homes.

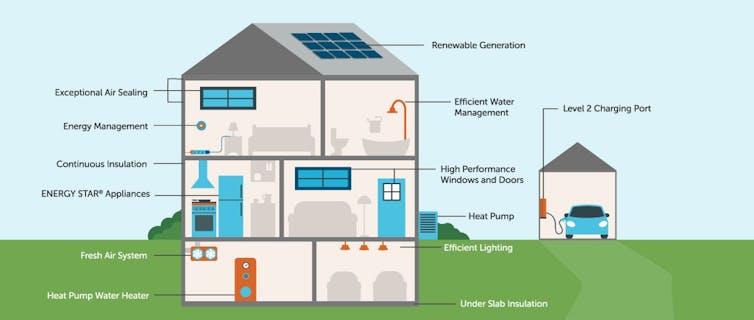

Installing more-efficient furnaces, better insulation and smart thermostats are helpful first steps, but getting close to zero will require switching to electricity for space heating and water heating. In the U.S., 46% of homes use natural gas as their main source of heat, 40% use electricity, 10% use other fuels such as heating oil or propane, and 4% are unheated. For water heating, the percentages are 47% gas, 47% electricity and 6% other fuels.

Today, electric and gas heating have similar carbon footprints, since roughly 60% of U.S. electricity is generated from fossil fuels and many homes use inefficient electric resistance heaters. But the emissions intensity of electricity is rapidly declining as coal plants close and solar and wind power expands.

President Joe Biden has set a goal of 100% clean electricity nationally by 2035. Although current federal policies fall short of that target, a growing number of states have committed to 100% clean electricity by 2050 or sooner.

Natural gas is far harder to decarbonize than electricity. Lower-carbon fuels such as biogas and hydrogen that could be blended in with natural gas are likely to remain scarce and costly.

Furthermore, advanced technologies enable electric heat pumps to heat both air and water far more efficiently than traditional electric or gas furnaces and water heaters. That’s why various scenarios for decarbonizing energy all envision a major shift to electric heat pumps. This transition is well underway in Europe and starting in the U.S.

Replacing existing gas furnaces and water heaters with electric heat pumps can be costly and complicated, though incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act can help. But if new homes are built fully electric from the start, they avoid the cost of installing natural gas hookups, and emit far less air pollution and fewer greenhouse gases throughout the homes’ lifetime.

New York City and more than 50 California towns, cities and counties have already banned gas hookups in new buildings. Elsewhere, 20 states have barred the enactment of natural gas bans.

Gas stoves are a big reason why.

The power of a slogan

“Most people don’t care how their water is heated or how their heater works, but the Viking stove in the kitchen, people have this visceral emotional attachment,” Michael Colvin of the Environmental Defense Fund told me in an interview for my book, “Confronting Climate Gridlock.”

That emotional attachment makes stoves a flashpoint in battles over climate policy.

“Cooking is the hill that the gas industry wants to fight on,” Bruce Nilles of Climate Imperative told me in a 2020 interview that foreshadowed the current skirmish. “They’ll say, ‘Do you want the government to take away your gas stove that makes you a great chef?’”

The American Gas Association has promoted the notion that gas stoves make skilled cooks since the 1930s, when it introduced the advertising slogan “Now you’re cooking with gas.” An AGA executive planted the phrase with writers for comedian Bob Hope. Soon it was picked up by comedian Jack Benny, and even by Daffy Duck. The phrase has also appeared over time in social media endorsements and hashtags.

Gas burners do provide more control than many stoves with electric coils, especially older models, which can be slow to heat up and cool down. Today, however, many chefs, consumers and experts say gas is no longer the obvious choice. Magnetic induction cooktops, which cook using electricity to generate a magnetic field, heat faster, control temperatures more precisely and use less energy than other stoves.

“There’s this big misconception that electric ranges don’t cook as well as gas,” Shanika Whitehurst, a member of Consumer Reports’ research and testing team, said in a recent article. “But the technology has improved to the point where electric and especially induction ranges and cooktops cook every bit as well, if not better than gas.” Consumer Reports ranks induction and some traditional electric stoves among its top-rated models.

Homes built today will endure far beyond Biden’s 2050 net-zero target. And the longer the gas-is-better myth persists, the harder it will be to fully electrify new homes from the start. As I see it, if “cooking with gas” keeps us tethering new homes to natural gas grids for decades to come, our health, climate and wallets will pay the price.

Daniel Cohan is an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rice University. This post originally appeared at The Conversation.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

6 Comments

The main issue with gas stoves is linked to fire hazard. According to the National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA), kitchen fires are the first cause of residential fires (an average of 550 civilian deaths, 4,820 reported civilian fire injuries, and more than $1 billion in direct property damage per year).

See https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Data-research-and-tools/US-Fire-Problem/Home-Cooking-Fires

In gas stoves, open flames act as ignition source for flammable volatiles produced during cooking by grease, oil, etc. so the likelihood to start a fire is significantly higher than in electric and induction stoves (no open flame that can act as ignition).

These reasons by themselves might justify banning of gas stove in residential applications.

The front page of the link you provided says the opposite: "Households that use electric ranges have a higher risk of cooking fires and associated losses than those using gas ranges."

Good catch! An electric element can indeed act as ignition source if it reaches glowing temperature, especially with exposed elements. The numbers gas vs electric fires might be skewed by the fact that in USA electric is likely more popular than gas. Anyway, this is a reason more to forget about gas AND electric and go with induction stoves

I've successfully ignited oil in the bottom of a frying pan with an electric stove, without any contact between the oil and the coil, just by heating it up to the smoke point and beyond to where it burst into flame. (I got interrupted when had just turned the stove on high to warm up the pan, and I became engrossed in the interruption, and left the stove on high unattended.)

A great new invention that I don't think is on the market yet is pans for induction stoves that have a Curie point at a good cooking temperature. If you heat them by induction beyond that point, they become non-magnetic and the induction heating become vastly less effective. So this sets a maximum temperature that an induction burner can't heat them beyond. You could have a pan that would allow you to reach the smoke point of vegetable oil, but never light it on fire, so you can fry things at high temperature without the danger of the fire I lit. Or you could have a pan that is calibrated to go to the ideal temperature for cooking pancakes. You put the burner on high and it will go straight to the point and hold that temperature as long as it takes to make a stack of perfect pancakes.

This article is very alarmist about gas stoves/heating, and just seems to just be pushing a very "green agenda" without all the facts. If you properly vent your kitchen stove when cooking, then it will have very little effect on indoor air pollution. Let's not forget that having proper home ventilation by itself will go a long way to remove cooking pollution by itself.

Furthermore, when you cook food, you create pollution no matter what method of heating you use. Cooking is simply a controlled "burning" of your food, which contains all sorts of organic and inorganic chemicals. So the cooking smell itself, while delicious is also a pollutant. But this is glossed over in the "greenwashing" attempt to portray anything but electric based heating/cooking as bad.

Another thing that people forget/gloss over, is the dependability and backup potential of natural gas. Your home loses power, but you can still cook your food and have heated water if you have gas, and you can even have electricity and heat with a backup whole house gas generator(and it's relatively affordable, between $5K - 10K for an average house), unlike "green" energy.

With an all electric house, losing power means you can't live there at all. Yes, you can invest $50K to have a 15KW solar array, and a large battery backup system. But, who really can afford that? Certainly not the average person who lives in an all electric house.

We grew in a gas cooking/heating home, where my Mom baked and cooked extensively.

There was no hood venting either. It was a house that was built in the 1928, so there was good air exchange from outdoors (it was leaky).

Yet, none of us three children suffered any ill effects, and neither did my parents. We are all healthy, and parents are 82 and 94 right now. Contrasting to today's kids, we ate good whole food Mom prepared. Our screen time was limited, as there was only so many re-runs you wanted to watch, so we ran around outside and got exercise. As a result, we were healthy, as were the kids around us.

Non-rhetorical questions:

What is the leakage rate overall for the natural gas distribution system serving residential areas?

My perhaps incorrect notion was that it was similar and percentage to the unburned methane rate of natural gas ovens and cooktops. But I don't have the data right now or studies support that. However, anecdata from my own house (itself dangerous notion in policy discussions) supports that the leakage rate is quite significant in the climate discussion. I recently discovered that my furnace was leaking gas due to a leaking valve- and my house is a very common type in my neighborhood with all similar systems and similar vintages. Also, my storage unit burned down several years ago due to a natural gas leak that was presumably going on for a long time, unnoticed, until it finally found an ignition source.

And then there's the Natural Gas Distribution Hub that I used to ride my bike by every day on my commute that always reeked of mercaptan. This all adds up to something more, but I dont know how much. Most people dont really care how their energy services are delivered (iso long as the beer is cold and the shower is hot), but cooking is an exception, and therefore a focal point here.

As homes electrify ( which was already a strong trend in my world as of a decade ago due to the superiority of heat pumps serving homes in the California energy market), how much longer is the utility world going to be able to rate-base the natural gas system to serve each home a therm or two a month for cooking. We might as well go LPG. Indeed that's what my household has done for the few times we want to cook with our trusty old wok.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in