I recently finished writing the chapter on the interaction of structure and control layers in my book. The last part was on the various ways to insulate the top of a house. The most common, of course, is to have a vented attic with insulation on the attic floor. But when you visit discussion forums like those hosted on Green Building Advisor and the Journal of Light Construction, you’ll find a lot of talk about putting the insulation at the roofline. And you can end up really confused.

When you move the insulation to the roofline, things get more complicated. You can put all the insulation on top of the roof deck, all the insulation on the underside of the roof deck, or some on top and some below. You can put it all below the roof deck but use two different kinds. Your insulated roof can be a cathedral ceiling or it can be above a conditioned attic. You can vent the insulated roof assembly or build an unvented insulated roof.

But what’s the best way or the safest ways to insulate the top of the house? I spoke with Kohta Ueno of Building Science Corporation about this topic and put that question to him. Here are his top three methods:

1. Vented attic

This one’s the most common and the least likely to cause problems . . . if you do it right. A lot of houses with vented attics in cold climates have problems with condensation in the attic or ice dams on the roof, but those are failures to air-seal and insulate properly. When you get the air leakage and conductive heat loss low enough, those problems disappear.

What to do with the heating and cooling equipment and ducts is an important issue to address, though. If you’re going to do a vented attic, you’ll want to keep all of that out of the attic. It’s possible do this well with deeply buried ducts, and my contractor friends out West do this a lot. But in a humid climate, burying ducts increases the risk of condensation.

When you go this route, you get another benefit, too. Vented attics are the least expensive way to insulate the top of the house.

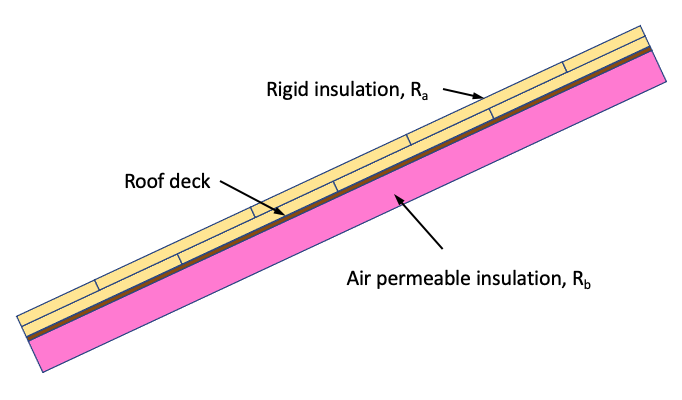

2. All exterior insulation on the roof or some on top with fibrous insulation beneath

Second on Kohta’s list is putting all or some of the insulation on top of the roof. This keeps the roof sheathing protected from moisture damage because it stays warm. You can use either rigid foam or mineral wool on top of the roof deck.

If you go with a hybrid assembly, Kohta recommends using fibrous insulation on the underside. You could use open-cell spray foam there, but cellulose or fiberglass would be much less expensive and do the job just as well when installed properly. The key with a hybrid assembly is to follow the ratio rule to make sure you have enough insulation on top to keep the sheathing above the dew point.

With insulation on top of the roof deck, you don’t want any venting at the roof deck. You can put ventilation channels above the topside insulation if you’d like, but don’t vent below the insulation. It will reduce your R-value.

3. Closed-cell spray foam insulation beneath

The third way is to use closed-cell spray polyurethane foam on the underside of the roof sheathing, which creates a conditioned attic. Closed-cell is the best type of foam to use here. It works in every climate because it’s a class 2 vapor retarder, which will protect the roof sheathing from moisture damage. Just be sure to put enough insulation on the roof, get it sealed and insulated properly over the exterior walls, and provide a bit of conditioning for the attic.

There you have it. Insulate the top of the house using one of these methods, and you can be confident that it will work well if you do it properly. When you get into other assemblies, the risk goes up. That doesn’t mean you can’t do them. I have open-cell spray foam on the underside of my roof deck. You just need to be extra careful.

_________________________________________________________________________

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and founder of Energy Vanguard. He is also the author of the Energy Vanguard Blog and is writing a book. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

26 Comments

Seems to me you glossed over the biggest disadvantage of moving the insulation to the roof line. That is if somehow you do manage to get the same R value at the roofline (This is no small feat) the house will still lose about twice as much heat out the top because the roof has twice the surface area as the attic floor.

An R60 roofline is almost unbuildable and unaffordable while 19 inches of cellulose is cheap and easy and works 50% better.

Walta

Hi Walta--definitely agree that a vented attic is way more cost effective to get to R-60, compared to the crazy-town of trying to achieve R-60 in a sloped assembly.

However, a correction on the house will still lose about twice as much heat out the top because the roof has twice the surface area as the attic floor. You definitely are increasing your surface area, but not by that much--I have those values calculated out from back when I was doing area takeoffs on a regular basis. A 12:12: slope (typically the steepest you would see) is ~40% more surface area than the flat attic floor below. Of course, if you have anything other than a hip roof, your surface area is also increased by exposed gable ends.

Overall, the only reasons to insulate at the roofline are (a) ducts are up in the attic, and they're not going anywhere else and/or (b) living space program is built up into the sloping roof spaces--a relatively common condition in the Northeast and Midwest at least.

I keep reading that you can vent over exterior rigid foam "if you want" but it's not clear when exactly it's a good idea in a heating climate. I'm in Zone 5 northwest Massachusetts looking to put about R40 of rigid foam polyiso on top of roof sheathing with about R19 of fiberglass batts between rafters underneath. Thinking peel and stick over original board sheathing as air barrier. I could lay 2x4s on flat vertically over rigid foam and beneath second layer of sheathing to create vent channels or put sheathing right over rigid foam without vent channels or put 2x4s on flat horizontally as purlins for roof with no sheathing. I am assuming with R40 above sheathing and peel and stick air barrier there's little chance of condensation in attic, but is over venting a good idea under a metal roof that might have condensation under it? It's a steep 12:12 roof if that makes any difference.

You will be fine with that. In my retrofits, I usually put four 2" layers of EPS on top (over peel & stick Mento)and we've been checking in all unfinished areas over the years for moisture build up above the interior fluff insulation and so far none. Dismiss the shims under the 2x4s in the photo as we had a 3" swayback in the 1920 2x4 rafters that the owners did not want to see anymore.

Stolzberg,

I suspect there is contradictory advice because the preferred methods are all based on our suspicions, not good data or experience. But also that it doesn't matter much either way as long as it is detailed appropriately.

I don't like creating cavities between metal roofing and the sheathing below. My thinking is: no air-space, no air to create condensation. I also see a lot of details for this secondary vent channel that include no real provision for an air intake or exhaust, or what happens to any moisture that needs to drain at the eaves.

Against that is: If things do get wet, with a permeable underlayment, you will have some drying. And, building over exterior foam, you need strapping to attach either the sheathing or roof panels, so you may end up with a cavity regardless, and might as well detail it to aid drying.

Thanks. Can you clarify why you need strapping over exterior foam? A lot of the unvented roof assemblies I've seen show second layer of plywood sheathing screwed directly through rigid insulation to the rafters.

I have essentially two large dormers on either side of straight gable roof, so four long valleys make venting difficult. If I do vent, does it make sense to run flat 2x4s diagonally, parallel to valleys?

Typically exterior foam is thick enough that you need structural screws to attach through it. The fastener schedule for sheathing would mean using an awful lot of them, whereas if you use strapping the sheathing can be nailed off. If the foam is thin enough to attach the sheathing directly, I don't see a problem with doing so.

Strapping diagonally is another thing I'm not convinced by - but again, just based on my personal prejudices rather than any data. If the idea is to promote air-movement, I'm not sure you get appreciably more that if the strapping were installed horizontally (what's the force that is supposed to be causing the air-movement in these channels?). If it's to provide a drainage path, what happens where the strapping terminates at the gable ends, and how is the drainage dealt with at the eaves?

Will there be sufficient moisture to need draining? Will this moisture follow the diagonal pathways, or will it go straight down and saturate the bottom of the strapping? My feeling is that the small amount of moisture that will condense on the back of the roofing should be able to dry through the raised profiles of the panels.

Would solution #2 (exterior insulation on the roof) also solve issues caused by knee walls?

Drew: Yes, insulating the roof deck would turn attic kneewalls into partition walls.

The insulation/roof should be airtight, correct? So the areas behind the kneewalls and above the attic living space will be unvented?

Are there any other considerations to keep in mind? What are the details at the soffit?

The attic above the half story has ventilation. If I replace the roof with #2 (unvented assembly) then I should remove the existing ventilation, correct?

Drew, it does as long as you can properly seal and insulate any dormers they are associated with. If they are just lower internal walls in a conditioned attic space, everything is warm behind that knee wall and can then be used for storage.

A general comment on 'roofs that I like' and 'over-ventilated roofs' (air channel above), that I previously sent to Dr. Bailes, for reference:

As a bonus round: any of the “over ventilated” compact or cathedral roof assemblies out there are a step up from Roofs 2 and 3, durability-wise. They provide both a compact airtight assembly, plus the durability benefits of a ventilated space. For instance, see Joe Lstiburek’s roof for avoiding ice dams (BSI-046 below), Ben Bogie’s over-ventilated roof, or Chris Corson’s/EcoCor’s roof assemblies. They allow for drying of the assembly into the ventilated cavity, reduce risks of ice damming, and create a “secondary roof” underneath your primary waterproof membrane. Ideally, if/when your primary waterproofing fails, water will only leak into the ventilated cavity, run downhill, and hopefully somebody will notice dripping or icicles where they’re not supposed to be, and know to fix the roof. However, any of these options are a substantial shift in complexity and detailing—I don’t see production builders implementing any of these, for instance. But if you wanted a compact assembly plus great durability, this is a Lexus approach.

BSI-046: Dam Ice Dam

https://www.buildingscience.com/documents/insights/bsi-046-dam-ice-dam

EcoCor-Roofs

https://ecocor.us/roof-systems/

Seems to me that once you have sheathing/foam/sheathing (as in the drawing), you might as well use it structurally - ie a SIP.

Hi Jon! Just to clarify, the assemblies I'm specifically talking about here are ones with an ventilated air channel--a SIPS, by itself, does not have that. There are plenty of cases of adding a ventilated air channel over a SIPS panel--that is often done if you are trying to get the best moisture safety out of a potentially risky roof (SIPS), and/or you are trying to solve existing moisture problems in a SIPS roof (ridge rot, shingle ridging, etc.). Martin Holladay did a nice job showing an image of this lay-up in a FHB column, per the image below.

That being said--with a ventilated channel SIPS roof, you're installing three layers of structural sheathing at that point--two on the SIPS, and then the nail base for the shingles.

Air-Sealing SIP Seams

Houses built with structural insulated panels require unique methods of air-sealing to ensure an airtight thermal envelope.

https://www.finehomebuilding.com/project-guides/insulation/air-sealing-sip-seams

In reference to your first solution, you state that "A lot of houses with vented attics in cold climates have problems with condensation in the attic or ice dams on the roof, but those are failures to air-seal and insulate properly". You also state that one possible solution to avoid condensation is to deeply bury the ducts.

I found a great solution for separating the attic from the heated living space in this Fine Homebuilding article by Josh Edmonds.

https://www.finehomebuilding.com/project-guides/insulation/simple-air-sealed-ceiling-for-a-high-performance-home

Essentially, he puts sheathing on top of the attic floor joists and then puts the attic trusses on top of the sheathing. The attic space is now completely separated from the heated living space below.

All the ducts are run within the attic floor system (which is within the heated envelope of the house) so there is no heat loss to the attic and no condensation issues.

Can the attic trusses be designed knowing that they will sit on a such a base? Ie, with less or no wood in the bottom cord plus some brackets to attach the truss to the attic floor?

It's a great system if the project budget can absorb another whole (largely redundant) floor system.

You do not exactly need a sheating on the attic floor joists - a heavy duty reeinforced vapor retarder/airtight membran will do that for you. Yes, you loose the racking strength and cannot walk on it. Structually speaking the bottom cord of the roof trusses are better also connected to the top plates of the walls in a way so that the attic joists can lend a hand.. The load of the cellulose is not a problem for such membrans like a Intello plus or similar ones from Siga.

Bas,

If you take away the subfloor, what do you really have left? A service plenum made from very expensive I joists. If you are going to use this detail I think you have to go all in.

Interesting article, I guess the air-handler is inside the conditioned space somewhere, not the attic? It's not fitting in the 11" cavity so you're giving up an interior room/closet.

I contacted the author of the FHB article and he said that the truss manufacturer wanted the trusses installed on a 2x6 running around the perimeter of the attic floor system. He said they wanted their trusses to be able to flex without them putting any additional weight or stress on the floor system (the trusses were tied together using bracing like in a traditional attic).

I like this method of building since you can install ducts, water lines and pot-lights within the floor system and yet never puncture your air barrier (which is the attic floor sheathing)

I have personally done an install similar to this using 2x8's and OSB. We based it on one of Chlupp's designs. Originally, we wanted to do it with 2x4's to just simplify electrical and framing, but the municipality balked at the idea. Scheduling, construction politics, etc. meant that it was better to just do an OBC approved floor and get the project going. The truss manufacturer did not require the extra 2x6 rim and the local municipal framing inspector was fine with not screwing the drywall to the bottom chord as we made sure the truss manufacturer had a 2x4 bracing schedule. SW Ontario for reference. Truss installation was hugely simplified (it eliminated the crane rental as our zoom boom got them high enough we could slide them wherever was needed). Things learned from the endeavour:

-strongly considered rafters or attic trusses with an insulated roof for future designs after all was said and done (if you're going to build a floor, may as well use it; looking around in the attic, you began visualizing an extra office, etc. with a fire code egress window in the gable)

-framing, electrical, air sealing, and HVAC were simplified which, in theory, reduced labour costs

-secondary water barrier to the interior is nice (we put a vapor barrier on top of the OSB to placate the inspector)

-tough to pencil out the cost advantage/disadvantage on it (installation was done during the COVID lumber spike which.....sucked)

This was a great summary piece of major options. For retrofit situations, usually the insulation above the roof deck option is hard. That leaves spraying the underside of the roof deck with closed-cell or air sealing/adding more cavity fill above the ceiling. The former being unvented and latter being vented. The latter doesn't work if HVAC is up there and a retrofit could never bring ductwork inside w/o costly interior re-work. Lstiburek describes a double-roof design that hybridizes vented and unvented but that wouldn't work for a retrofit unless you're redoing the whole roof deck which is hard.

So, for a retrofit with ceiling HVAC, what about a poor man's hybrid retrofit version with foam paneling attached to the underside of the trusses, leaving the truss cavity vented but interior attic space "conditioned". Since r-values may be limited by how much foam paneling can be applied under the trusses, the loose fill insulation above the ceiling can remain (which saves work, adds r-value above the occupied space and also adds some sound transmission benefits and, if cellulose, fire retarding).

This creates an attic space that is unvented, and while not fully insulated to code levels, warmer or cooler (depending on season) than exterior ambient temps which is better for the HVAC.

I'm planning our roof replacement here in Southern California and none of our attic or roof (built in the 1950s) is insulated. I don't like the idea of adding attic insulation and keeping it as a vented attic because we are continually doing a lot of rewiring to electric circuits and plumbing, and wouldn't want the insulation to bury all the wires. So I'm looking into insulation as part of the roof when the roof is entirely replaced.

My question is, what is the very best exterior insulation product, regardless of the cost? The technology is improving every year, but I'm not up to date on new products that may have been introduced recently that I may want to specify to the roofing contractor. Since this is a complete roof tear down and replacement, my roof is pretty much a blank slate to apply the best insulation technique out there.

Thanks Allison! Can you speak more to your use of open cell foam for your own attic and what details you’ve included to make this a “less risky” roof assembly? I’m trying to wrap my head around the best option for a client’s flat roof, rowhome attic space in PHL. It’s a 19” cavity with 6” rafters and 4” joists, leaving only 7” where they intersect. I’m leaning towards a spray under the roof deck but don’t think we can bring a rig into the neighborhood due to the narrow streets. Portable tanks will bring their own set of challenges, not to mention be very expensive. The pressure boundary along the ceiling could be air sealed in theory. Loose fill could then be blown in. But without any ventilation, I have concerns about what that roof deck might look like down the road. Insulating above the roof deck is out of their budget range for sure. What would be the best performing, most durable option that wouldn’t break the bank? Thanks in advance for your and the community’s thoughts!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in