ABOUT SITE DRAINAGE

We go to a lot of trouble helping our houses shed precipitation. Managing water that’s on the ground is no less important. Ground water flows on or below the surface; it rises and lowers depending on rainfall and can be controlled with subsurface drains. Surface runoff comes off the roof and other impermeable surfaces. A system of gutters, leaders, and drains can collect and direct this water away from the basement, protect vegetation, and prevent ponding in low-lying areas on the site.

Gutters are usually — but not always — a key part of this system. You can make in-ground gutters with a trench that runs along the perimeter of a foundation — a curtain drain of sorts — to direct water to a rainwater collection tank, a drywell, a rain garden, or other suitable spot.

MORE ABOUT SITE DRAINAGE

Hundreds of gallons of water can be collected for every inch of rain, even from a relatively small roof. When a storm drops heavy rainfall in a short time, the ground can become saturated, causing surface water to run off. This is when channeling gutter discharge well away from the house is most important. Short lengths of drainpipe — or worse, splash blocks below gutter downspouts — can still allow water to pool against foundation walls and leak into the basement.

This surface and near-surface runoff can also pool in low-lying areas on a building site or flood a sub-surface septic field. A few ways to intercept it:

Curtain drains, strategically placed trenches filled with permeable materials and perforated drainage pipes, can intercept ground water and direct it to an area where it won’t do any harm (see below).

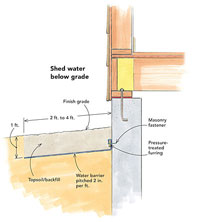

Below-grade flashing. An option for collecting all of the water from the roof without using gutters is similar in construction to a curtain drain. Variously called in-ground gutters, foundation flashing, and underground roofs, it’s basically a peel-and-stick membrane or sheet of plastic that runs down the foundation wall and then turns out and slopes away. This directs any surface water away from the foundation.

In his book _Water in Buildings_, William B. Rose describes another technique, a kind of subsurface roof that diverts water from the foundation. Far from taking credit for the idea, Rose says below-grade flashing was used on Gunston Hall, the 1750 Virginia home of George Mason, one of America’s founding fathers.

Attached to the house, then angled downward 20%

In its modern application, builders use a sheet of rubber or plastic fastened to the foundation at grade, take it down a foot, and then draw it outward for another 2 feet to 4 feet at an angle of about 20%. A layer of rigid insulation under the rubber or plastic sheet traps heat and offers some freeze protection for drain tile located at the outer edge of the flashing. The detail keeps soil next to the foundation from becoming saturated and may moderate moisture swings that lead to soil movement in expansive clay soils, Rose says.

Mulch, pea stone, or some other material that creates a variegated surface can reduce splash-back around the building perimeter below the eaves.

Rain gutters. No matter whether they’re made with metal, plastic, or wood, rain gutters are invaluable in directing rainwater away from the house. The two most common gutter profiles are half-round and the so-called K-style, produced mile after seamless mile by contractors with portable forming machines. Half-round gutters move water better than the flat-bottomed K-style.

Consider a soils report

Rather than fixing drainage or settlement problems after the house is built, a better method is to get a soils report from a qualified geotechnical engineer. An engineer’s report based on test borings or pits can detect problems like sub-surface water, uncompacted fill, and poorly draining soils before excavation. On flat, well-drained building sites, a pair of test pits five to eight feet below the proposed footing depth at opposite foundation corners may be enough, but intermediate pits may be required on hilly or wet sites.

Deeper borings (25 feet or more) may be necessary on unusually steep sites or when pier foundations are planned. Deeper pits can detect the presence of bedrock and sub-surface water moving horizontally.

Control erosion during construction

It’s important to control surface water during site clearing and foundation excavation to prevent soil erosion, which can clog streams and damage aquatic ecosystems. Implement an erosion-control plan before construction begins. Most plans will incorporate vegetated buffer zones and erosion-control measures like hay bales, silt fencing, or wattles. The Environmental Protection Agency also suggests staging construction during the driest part of the year when possible, and clearing only the areas required for construction.

Snow fencing, solid fencing, and hay bales are all effective at reducing wind erosion. Periodically wetting the soil is also helpful. Use reclaimed topsoil to get grass and plants growing again at the earliest opportunity to minimize both water and wind erosion. You can prevent heavy equipment and vehicles from damaging newly planted areas by cordoning them off with temporary fencing.

Erosion mats made from natural fiber are a good option for stabilizing slopes or stream beds after planting. The material eventually breaks down, but not before roots have taken hold to prevent erosion.

Bird’s View

Image Credits: Martha Garstang-Hill/Fine Homebuilding #189

Roof gutters, curtain drains, and slope are key

There are two things to think about in keeping a site dry: water coming off the roof; and rain soaking into everything else that’s at site level or higher. Consequently there are two drainage systems — one for gutters, and one to keep the immediate area clear.

In small yards or those that are not configured for a rain garden or drywell, getting gutter runoff “to daylight” is an absolute minimum. This means that gutter drainpipes are terminated above-ground to let them empty above ground. Many local codes specify at least five feet away from the house without also specifying “and downhill.”

Avoid runoff in the streets, recharge the ground water

As land gets developed, rainfall is increasingly diverted from ground storage and directed to storm drains. This further depletes ground water supplies, overtaxes city sewer systems, and dumps lawn fertilizers, pesticides, and pollution from streets into rivers, lakes, and oceans.

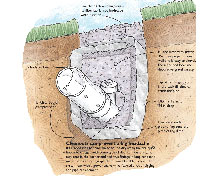

Worm’s View

Image Credits: Martha Garstang Hill/Fine Homebuilding #189

Sometimes it’s the water you don’t see that does the damage

Keep the foundation dry. Build to keep water away from the house but retained on-site. Different types of drains incorporated in to the landscape and house can carry bulk water away from a house to keep it dry.

A curtain drain is like a gravel-filled moat that protects a house from ground water. These are a good solution for houses with hills behind them that constantly keep the basement damp.

Inside the moat is a perforated pipe. When water comes down the hill just below the surface, it runs into the gravel, fills up the pipe and is carried away to daylight, drywell, or rain garden.

Key Materials

Image Credits: Krysta Doerfler/Fine Homebuilding #189

Choose materials well, you won’t see them for a while

Gravel: 3/4-in. gravel percolates well and is easy to shovel. For a finished look, top with decorative gravel.

Drain pipe: Solid PVC is best; black flexible pipe is easiest and least expensive.

Filter fabric: Avoid generic landscape-type weed-blocking fabrics; they won’t last. Instead, choose high-quality landscape filter fabric such as Typar.

Design Notes

Surface drains are part of the landscape, so why not treat them that way?

A curtain drain or other stormwater diversion doesn’t have to be an eyesore. Make them focal points, or even integrate them into other garden features.

Paving and drainage choices need equal consideration. It’s an integrated issue because the paving material has to work with the building and landscape design, and may need to be coordinated with the interior design as well. Paving has green building implications in two areas: First, production effects (whether it an environmentally preferable material, e.g., recycled content, salvaged, etc.); and second, performance effects such as heat island (the reflectivity/emissivity of the material) and stormwater absorption/retention (the permeability of the material).

Images from: Fine Gardening.

Builder Tips

##Pitch drain lines, and don’t forget the cleanouts

In general, pitch the pipe away from the area that you want to dry out. Adding cleanouts to the pipe can save big headaches later on. Using sanitary Ts in the corners and Y fittings in the long run will make it easier to clear clogs with a power snake, saving on digging and replacing pipe. Flexible black pipe may not stand up to the power snake.

The end of the drainage pipe should be covered with hardware cloth or something similar to keep rodents out. Stone, brick, or concrete block placed under the outfall will prevent water from eroding soil.

Quick tip: Photograph or mark the locations of the cleanouts. It may be a handy thing to know when it counts.

Code

Build so water flows away from the house

The IRC requires that the foundation be high enough above-grade to allow positive drainage on all sides of the house [401.3]. The basic rule requires a slope of 6 inches for the first 10 feet of grade surrounding the house, with the surface drainage directed to a storm sewer or equivalent. The 2006 IRC allows exceptions if the building is too close to the property line or a physical barrier prevents a 10-foot slope. In these instances the grade can be 5% with the water directed to a swale [401.3X].

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

It takes more than a casual, one-time inspection to gather reliable information about water on a site.

Ground-water levels may change seasonally, as do rainfall patterns, so look to sources of local data to help predict water flow on the property at different times of the year.

Flood maps on file at the local building office are a good first step. Weather service records and even back issues of the local newspaper also can yield useful information.

“Fin” drains, high-tech variations of curtain drains, are faster and easier to install because they require less excavation. They consist of a geotextile composite and solid or perforated drain line, and can be installed in a much narrower trench, eliminating the need for stone aggregate. At the moment, they’re more common on civil engineering projects than in residential applications, but that may change.

DEVIL IN THE DETAILS

Gutters won’t do much to direct water away from the foundation if they leak or are installed poorly. Make sure to seal connections.

KEY CONCEPTS

In rainy climates, a site-drainage system can keep a house dry. Design strategies that can control stormwater runoff:

* Roof overhangs

* Sloped ground

* Strategically placed landscape drains

8 Comments

Stormwater Drainage

Good comments on drainage. In my practice as a forensic architect I see dozens of site drainage problems every year that are causing significant damage and are easily solved by one or more of the methods you describe.

In the Historic District of Louisville, Kentucky, where I live, I am now combining roof water drainage with geothermal HVAC systems. When augering wells for our systems, we encounter sand at about 10 to 15 feet below grade which continues to bedrock at about 110 feet. After installing the closed loop geothermal piping, we backfill the wells and the piping trenches that connect them with gravel. Over this we install perforated PVC pipe and connect this with rigid PVC pipe to the downspouts from the house. All of the roof drainage is dispersed over the trenches and finally down the wells. Even in recent 100 year storms, the system functioned perfectly. There may be areas where this system does not function as well, so I would always suggest you talk with the drilling crews before hand to they can give feedback on what is encountered and at what depths.

Our houses are 1880 to 1910 vintage with limestone block foundations that are notoriously leaky. Where I have combined this system with a french drain to catch surface water, damp basement walls have been virtually eliminated even in the worst of storms.

isn't it best to go below the foundation footing?

Just yesterday I looked at a house with the new home buyer and a mold specialst. It had a lot of site drainage problems and a wet basement (but no standing water after the recent big storms in eastern MA. There is a hill behind the house, and some regrading needs to occur to move the surface run-off around the house. The owner then wanted to install a shallow curtain drain on the back side. The mold man said it needed to go below the footing (which is my take as well), to deal with hydrologic pressure from subsurface water. He suggested an interior french drain cut into the basement slab perimeter so we aren't excavating 8' deep at the outside of the field stone foundation. Is there any reason that we should consider the exterior shallow curtain drain that you illustrate instead?

It's a cost issue

Laura,

Every site is different. On some sites, a shallow French drain used to intercept and redirect surface water can dramatically improve conditions in a basement. On other sites, the only way to handle all the water involved is with a perforated drain at the level of the footing.

In most cases, a shallow French drain is much cheaper than a new footing drain, so often that solution is tried first.

A neighbors problem

I have a next door neighbor who has a problem with water getting into his basement. He has placed drainage piping from all his down spouts aroud to the back of his house. his back yard slopes gently toward my yard. The distance between his house and mine is only about 30 feet. He directs one or both at times toward my yard that during a 4" rainfall the water can roll right past my back basement window. No problem has occured as yet. My question, can he intentionally direct storm water from his property to mine. I have not dicussed the point with him due to his questionalble behavior. I was a plumbing designer in my younger day and I remember some things and am not sure about all when it comes to storm water run off.

Thanks

This really isn't a green building issue

Anonymous,

This is a legal issue, not a green building issue. To get an answer to your question, you need to talk to your town officials or a lawyer.

Directing stormwater drainage on to a neighbor's property

Many jurisdictions legislate through the zoning ordinance that one is responsible for causing this problem to an downslope neighbor. The zoning ordinance is typically administrated by the county level of government, where enforcement is by the sheriff's department and has a pretty low priority. If damage is severe, the common law may be a resource but one must show actual damages. However, legal expenses may outweigh thedamage costs. If they are available, the services of a community mediator may be the most civilized way to reconcile such disputes.

High water table

The site I am considering making an offer on is table flat, small (0.6 acres) and reportedly is in an area with a high water table. I am going to put in a contingency to have a test pit done to measure the water table level. If the water table turns out to be high, am I better off just building on a slab (everyone around here (upstate NY) has basements) or doing a basement? What could we do to keep the water out of a basement on a site like this?

Response to Elizabeth Kormos

Elizabeth,

The standard solution to your dilemma (building a house on a site with a high water table) is indeed to build on a slab. It's perfectly possible to include enough above-grade rooms to accommodate the usual functions of a basement: a mechanical room for your furnace and water heater, for example, and a large storage closet for your Christmas ornaments.

You should consult a soils engineer before proceeding.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in